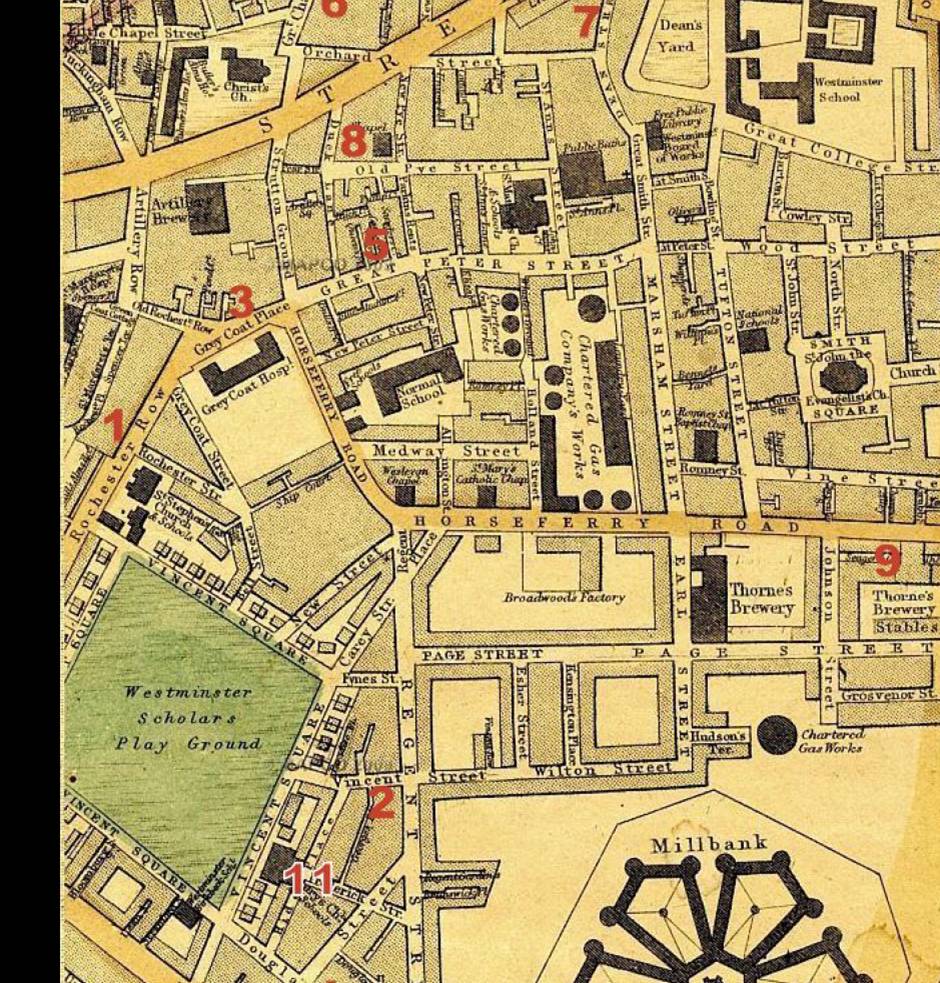

Fig. 26: Part of Westminster (from Weller’s

1868 Map of London) © Mapco

Westminster Abbey, St. Margaret’s Church, and

Parliament are in the upper right, Millbank

Penitentiary in the lower center and Vincent Square in

the lower left. Locations mentioned in text: Rochester Row (1), Vincent Street

(2), Grey Coat Place (3), Douglas Street (4), Queens Place (5), Dacre and Great Chapel Streets (6), and Dean Street (7),

Bow Street/Thieving Lane (10), and the Church of St. Mary, where Daniel and

Maria were married, and where his mother was vestry-keeper (11). The foreground

of the drawing ofthe Devil’s Acre in Fig. 35

corresponds to the (8) on this map. By 1868, Market Street (9) was part of the Horseferry Road. The map depicts an area of about 1 km x

1.1 km – north is towards the top of the map.

The following is extracted from the current

working draft of my narrative of the family history of my four paternal great

grandparents William Duke, Ellen Reeves, Daniel Blackford

and Maria Dinham. This extract describes the Maria Dinham’s family. Her life following her marriage to Daniel Blackford in 1861 is described elsewhere in the narrative.

In summary, he was a gunsmith and member of the recently established Corps of

Armourer Sergeants. He was assigned to the 1st West India Regiment in October

1863 and the couple spent the next seven years in various Caribbean garrisons,

including Jamaica, Barbados and the Bahamas. None of the three children born in

the West Indies survived. Daniel and Maria returned to the Vincent Square

neighbourhood for a year’s furlough. Daniel then spent a year at the small arms

factory in Birmingham, and in 1872 was posted to the Canadian Militia in

Montreal. The family remained in Montreal following Daniel’s discharge.

Beatrice, the couple’s only surviving child, married William Duke and they were

my paternal grandparents.

The Dinham

Family

My great grandmother Maria Dinham (Fig. 31) was born in 1841 in the same Westminster

neighbourhood as Daniel Blackford, her future

husband.1 She was the youngest of the nine

children of John Dinham and his wife Johanna Jackson.

John was the son of Thomas and Susannah Dinham.2 The latter are my earliest proven Dinham ancestors.3

Thomas Dinham

was born in about 1757. 4 Although his

birthplace is unknown, numerous records indicate that he spent his adult years

in London, living within a block or two of Westminster Abbey. He was recorded

as a Master Shoemaker in the parish of St. Margaret in 1779.5 There is a second entry in the same apprenticeship book, dated six

weeks later, for Thomas Dinham, Master Cordwainer (Originally, ‘cordwainer’ denoted those

who made shoes from cordovan, a soft type of new leather from Spain, but by the

19th century it had become synonymous

with ‘shoemaker’. A ‘cobbler’, by contrast, repaired shoes.) in the parish of St. Marylebone.(6)

These individuals may have been

unrelated, which seems unlikely. Given that stamp duty on apprenticeships was

often registered well after the fact, it is possible that both records refer to

the same man (although why “shoemaker” in one and “cordwainer”

in the other?). Alternatively, perhaps the second entry referred to a father or

cousin. Two subsequent references in court records list Thomas’ abode more

specifically as Bow Street, St. Margaret Westminster. In 1784 he petitioned the

court seeking to reduce the fine levied against Mary Ford, a poor woman

convicted of assault,7 and later, in 1790, he was a member of a coroner’s jury. 8 Similarly, Westminster Rate Books place him in Bow Street from

1786, at the latest, until about 1815. In some years he occupied two properties.(9) Whether he owned

one or both of these premises is unclear, although notations in two instances

suggest that he was a tenant. Some records locate his premises in “Bow Street

West”, which would have been near the point depicted in Fig. 33. Bow Street no

longer exists, having been built over by government buildings, and was distinct

from the eponymous thoroughfare in Covent Garden. Back in the day, it was a

short street that skirted the grounds of Westminster Abbey. It had previously

been known as Thieving Lane because convicted felons were taken by this route

to Gatehouse Prison, which stood in front of the Abbey until 1776, lest they

seek sanctuary on the church grounds. This was an insalubrious neighbourhood.

According to the creator of the etching in Fig. 33, “The inhabitants are of the lowest

order, & aggravate, by their numbers, that nuisance which the filthiness of

their persons & the narrowness of the avenues had already created.”

I have yet to find a record of

Thomas and Susannah’s marriage or of her maiden name. She was apparently born

in about 1768. 10 Given that the

average marriage age for women of the period was 23, the couple likely wed not

long before the birth of their first child in 1794. However, it is possible

that Susannah was not Thomas’ first wife. A Thomas Dinham

married Joan Mudford in Westminster in June 1778 but

no other evidence has surfaced to confirm this.11 The St. Margaret parish register indicates that Thomas and

Susannah Dinham had at least seven children. The

eldest was my 2x great-grandfather John Dinham, born

in 1794. He was followed by George (1795), Elizabeth (1796), Thomas (1798),

Sarah Jane (1799), Susannah (1803 - 1805), and Susannah (1806).12 The register also records the burial

of a Thomas Dinham in 1796. This may have been a son,

but no baptismal entry has been found. Perhaps this was Thomas’ father? Tax

records indicate that the Dinhams moved from Bow

Street to nearby Dean Street in about 1815.13 The latter is now

part of Great Smith Street, not to be confused with Dean Street in modern Soho.

There is an interesting reference to the Dinhams

during this period in the records of the Old Bailey. In 1818, Thomas Jr. was a

prosecution witness in the trial of a fraudster who had purchased a pair of

shoes from the Dean Street shop with a counterfeit £1 note.14 Thomas voted in the 1819 parliamentary election, which in

Westminster was a right accorded to males who paid the poor rate and did not

require property ownership. 15 The Dinham’s were living at 7 Dean Street when Thomas Sr. died

in 1822. It appears that his widow continued to live there until at least 1829,

following the marriage of daughter Sarah Jane. At the time of the 1841 census,

Susannah lived in Great Chapel Street with daughter Susannah and son-in-law.16

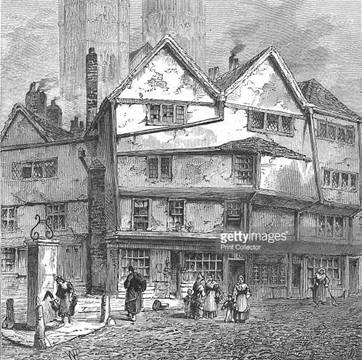

Figure 33: Bow

Street (Thieving Lane), Westminster 1808

“View of Broken Cross at the

southern end of Thieving Lane, Westminster; a woman fills a kettle from the

well, the buildings beginning to appear dilapidated, two

towers of Westminster Abbey rising in the background.” Etching

and aquatint, John Thomas Smith in “Antiquities of Westminster 1808”.

© The Trustees of the British

Museum

Museum No. 1880, 1113.2588

The Dinham’s

two eldest sons, John and George, followed their father into the shoemaking

trade. George appears to have remained in the Westminster neighbourhood until

his second marriage in 1846, but by the time of the 1851 census, he was living

on the other side of the Thames in Southwark.17 Thomas Jr. described himself as a “gentleman” in his children’s

baptism registration in 1831, seemingly unlikely given his residence in Grey

Coat Place.18 In the 1841

census he was described as a clerk and in 1851 as “Attorney’s Managing Clerk

and Accountant”.19 The Dinham’s daughters Elizabeth, Sarah Jane, and Susannah

married William Grinfield,20 Jacob Kitch,21 and Edward Bull, respectively.22 The

latter died not long after the marriage,

and Susannah then married Daniel Bull, a butcher and presumably her late

husband’s brother.23

In his will, Thomas Dinham left his “personal estate” to his wife Susannah,

giving her discretion to distribute parts to their six surviving children as

appropriate.24 Further, he appointed two friends as trustees of his “freehold estates”

to be managed to the benefit of his wife. Why these were not bequeathed

directly to his widow is unclear. In any case, the will does not specify the

location or extent of this property or indeed whether it included the Dean

Street premises. However, tax records from as early as 1821 indicate that he

owned several houses or cottages in Queen’s Place, a short lane off Great Peter

Street, on the edge of the “Devil’s Acre”, one of London’s most notorious slums

(see map in Fig. 26). In most years, the rate books listed seven residences in

Queens Place and it appears that the Dinhams owned as

many as six of these at various times. Following Susannah’s death in 1846, rate

books indicate that John owned nos. 1 and 7 Queens Place, Thomas nos. 5 and 6,

George no. 3, and son-in-law Daniel Bull no. 2. There is no indication that any

Dinhams ever resided in Queens Place. Judging from

nominal rental values of £3 to £5 per year, these were very modest accommodations:

by comparison, the Dinham residences in Dean Street

and Grey Coat Place were typically assessed at £15 to £20. After John’s death

in 1848, his two Queens Place properties appeared under Johanna’s name until at

least 1869.

John Dinham

married Johanna Jackson at St. Martin-in-the-Fields in 1819.25 She was very likely the daughter of

Joseph and Mary Jackson, but I have no further information about her parents.26 Tax records indicate that the Dinhams

lived in Rochester Row until about 1822, in Horseferry

Road until at least 1835 and afterwards in Grey Coat Place. It seems that for a

time Grey Coat Place was regarded as an extension of Horseferry

Road, and it is likely that the two locations were one in the same. The Horseferry Road dwelling had been occupied previously by

Johanna’s father Joseph Jackson. John and Johanna had nine children, the

youngest of whom was my great grandmother Maria Dinham.

Although tax records indicate that the Dinhams lived

continuously in Horseferry Road/Grey Coat Place from

1822, baptismal records for two children give their abodes as Lambeth Walk in

1826,

and Broadway in1828.

At the time of the 1841 census,

the Dinhams were living with six of their children in

Grey Coat Place.27 Maria’s two

eldest brothers were boarding elsewhere. Her sister Susannah resided across the

street in the Grey Coat Hospital28, a Church of

England charity school founded in 1698 to educate “the poor of the parish so that

they could be loyal citizens, useful workers and solid Christians”.29 Grey Coat is now one of London’s top comprehensive girls’ schools.

Although it still gives priority to disadvantaged children, many students are

well-off, including, for example, the daughter of British Prime Minister David

Cameron.

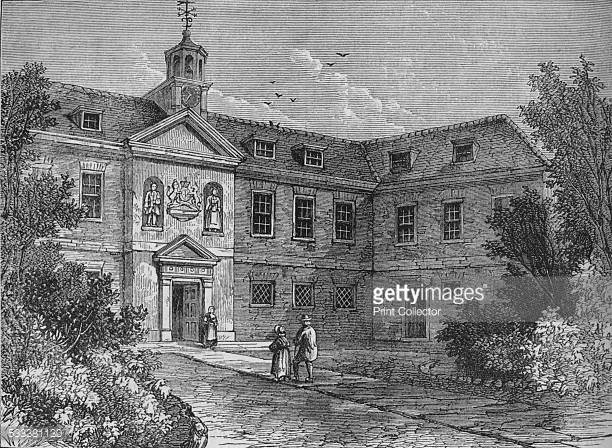

Fig 34: Grey

Coat Hospital

A charity school run by the Church

of England as it appeared circa 1878. Nine year old Susannah Dinham resided here at the time of the 1841 census whilst

her family lived across the street. Original sketch from Walford (1878). John Dinham died in 1848. At the time of

the 1851 census, Maria, her brother Joseph and her mother were living with her

brother Henry, his wife and daughter in Grey Coat Place.30 Henry was a shoemaker like his father and Johanna and Maria were

described as “assistants” in the census. Maria’s 14-year-old brother Samuel was

apprenticing as a cordwainer with a Mr. George

Hilliard in Bulls Head Court.31 John, her eldest

brother, was living in nearby Great Peter Street in a “model lodging house”. In

the 1840s, organizations such as The Society for Improving the Condition of the

Labouring Classes began to renovate old houses to provide clean and safe

accommodation at a reasonable price. A typical design for single men would

incorporate 100 sleeping cubicles with common kitchen, living and sanitary

facilities.

By the time of the 1861 census,

Maria was living with her mother at 1 Douglas Street, within a block or two of

the Blackford household on Vincent Street.32 Her brothers William and Alfred, both shoemakers, were living with

William’s family in Gray Coat Street33, and John, now living with Alice, a needlewoman, was around the

corner at 8 Regent (now Regency) Street.34 Alice was possibly employed at the Royal Army Clothing Depot,

which had opened in 1858 on nearby Grosvenor Road. This facility, which was

seen as quite progressive in its day, employed over 1000 needlewomen. Maria’s

sister Susannah Dinham was probably in service in the

household of a Dr. Forster in Southwark.35 She was still employed by Dr. Forster as a nursemaid in 1871, at

which time the family resided in Upper Grosvenor Street, between Grosvenor

Square and Park Lane.36 She does not

appear in the Forster household or elsewhere in the 1881 census. In 1891 and

1901, a Susannah Dinham of the same age as our

relative was boarding in the household of a laundryman on Silchester

Road in Kensington and described as “living on her own means”.37

Two Dinham

households remained in the neighbourhood at the time of the 1881 census. Bootmaker Alfred Dinham and his

wife Hannah lived at 41 Douglas Street.38 The family of William’s son John, a painter, resided at 1 Douglas

Street.39 Maria’s brothers had all died by

1891, and none of the Dinham clan remained in the

Vincent Square neighbourhood. Several of the next generation had settled in

Lambeth, south of the Thames. As far as I can tell, none remained in the

shoemaking trade.

At least three generations of my Dinham ancestors were involved in shoemaking in London from

the late-eighteenth to the late nineteenth century, a period during which boot

and shoemakers constituted the largest group of skilled craftsmen in the

metropolis. The trade changed substantially during these years and a brief

summary provides useful context for this narrative.40

The traditional system of

production was dominated by small workshops comprising a master shoemaker

assisted by a few journeymen and apprentices, working side-by-side to complete

the whole process from buying and cutting the leather, to sewing, lasting, and

closing, to finishing and selling the footwear. The trade’s guild – the

Worshipful Company of Cordwainers – gave master

shoemakers the exclusive right to sell shoes but also dictated that they sell

only what had been made in their own shops. The production and selling of

footwear evolved through the eighteenth century, in part in response to the

increasing demand for readymade boots and shoes. Master shoemakers seeking to

expand production would outsource the less-skilled stages of the process

(sewing, lasting, and closing) to journeymen, who generally worked in their own

homes. They were paid on a piece work basis, typically using material supplied

by the master. Also, the ability of the guild to regulate trade had diminished.

The traditional restriction that shoemakers sell only what they made broke down

with the emergence of a wholesale market. It was not long before some shops

(and notably the large “shoe warehouses”) were subcontracting the entire

production process to shoemakers in the hinterland, where lower wages resulted

in lower costs. Northampton was a noteworthy center

of shoe “manufactory”. Although “country-made” shoes were less expensive, they

were also of lower quality, and “town-made” shoes still attracted the upper end

of the market.

In the early nineteenth century, “The wholesale trade mushroomed and

the greater portion of the craft degenerated into dishonourable trade”.41 The latter designation referred to the use of less-skilled and

unorganized workers, often under sweat shop conditions, to undercut prices of

the honourable trade. The number of shoemakers increased much more rapidly than

the population as a whole. Combined with lower duties on imported shoes,

especially from France, and repeal of longstanding apprenticeship restrictions,

this put downward pressure on wages. A series of strikes by organized workers

may have had the unintended consequence of encouraging the “slop trade”.

Fig. 35: The Devil’s Acre

Iconic engraving (publ. 1872) by

French artist Gustav Doré, looking eastward from

Victoria Street towards the Houses of Parliament. The dwellings in the foreground

and the chapel behind lay along the north side of Old Pye

Street (#8 in map, fig. 26) and were vestiges of one of London’s worst slums.

On the right are the Rochester Buildings, erected in 1862 on the south side of

the street as social housing. Queen’s Place, site of the Dinham’s

rental properties, was razed for expansion of the Rochester Buildings in 1885.

The latter are still standing and are now part of the Peabody Estates South

Westminster Conservation Area

By mid-century, journeymen’s

earnings had decreased to an average of perhaps 15 shillings/week, one-half to

one-third of the levels in the early 1800s. 42 In 1851, there were 36,000 boot and shoemakers in London, the vast

majority of whom worked alone or with one or two assistants. Journeymen working

in their own homes often pressed their wives and children into service as

assistants in an effort to make a living wage. For example, as noted above, at

the time of the 1851 census, my great grandmother and her mother were both

living with her uncle and described as shoemaker’s assistants. The declining

standard of living took a toll: shoemakers were over-represented in various

negative social indicators including confinement to asylum and workhouses, and

charges of drunkenness, petty crime, and assault.43 By the late 1850s, with the advent

of the sewing machine, traditional methods were being supplanted factory

production of boots and shoes. We do not know for certain where our Dinham ancestors fit in this context. Thomas Dinham was a Master Shoemaker and, if not exactly

prosperous, accumulated sufficient capital to acquire the income properties in

Queens Place. The situation of his shoemaker sons and grandsons is unclear.

Were they journeymen or masters? Were they part of the honourable or

dishonourable trade? We do not know for sure.

1 Maria Dinham’s

birthdate was given in the 1901 census of Canada as

22 March 1841, whereas civil

registration index records it as the

April-June quarter 1841.

2 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, June 1794, unpaginated. Surname recorded

as “Dennum” in

register, but strong indirect evidence

that it is “Dinham”.

3 Determining the identity of my 3x

great grandfather was a challenge, but this is now reasonably certain

in light of diverse evidence from

parish registers, poll books, apprenticeship books, tax and court records, as

well as Thomas’ last will and

testament. Some of the initial difficulties arose from inconsistent spelling of

his

surname in some early records (e.g., Dinham, Denham, Durham, Dennum). Both Thomas and Susannah were

probably illiterate, which may have

contributed to the confusion.

4 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, Burials 1822, p.199, no.1591. Thomas Dinham’s age was given as

65, indicating

birth in about 1757.

5 1779 Board of Stamps

Apprenticeship Books, City (Town) Registers 1778-81.

TNA IR1/30/99.Thomas

Dinham Master Shoemaker, John Dinman Apprentice. 30 Aug 1779. [Was Apprentice “Dinman” actually

Dinham?]

6 1779 Board of Stamps

Apprenticeship Books, City (Town) Registers 1778-81. TNA IR1/30/108. Thomas

Dinham Master Cordwainer,

Charles Waller Apprentice. 13 Oct 1779.

7 1784 Middlesex Sessions of the

Peace: Court in Session, London Metropolitain

Archives Ref. No.

MJ/SP/1784/05/077.

8 Coroners' Inquests into Suspicious

Deaths 1790, Westminster Archives Centre, accessed through

London Lives Project (www.londonlives.org), Ref: WACWIC652300603

9 TNA: Surrey, Land Tax Redemption Office:

Quotas and Assessments, IR23; Piece: 55. Vol. 8, 1798.

10 Susannah Dinham,

age 78 yrs., buried 25 June 1846. Register: St. Margaret Westminster, Burials

1846,

p.46, no.363.

11 Westminster Marriages

Transcriptions: St. John the Evangelist Smith Square, 9 June 1778. (FMP)

12 Baptism Register: St. Margaret,

Westminster: John Dennam June 1794; George Denham

June 1995;

Elizabeth Denham July 1796; Thomas

Denham January 1798; Sarah Jane Denham August 1799; William

Denham Oct 1801

p.92; Susannah Denham January 1803 p. 145; Susannah Denham May 1806 p.283.

13 I have not yet completed my

analysis of the Westminster Rate Books which include numerous entries

for Thomas Dinham,

his wife and children. Interpretation is not always straightforward. It appears

that the

rate might have been assessed against

either the owner or the occupier of the property depending on

circumstances. Also, each book generally covers

more than one year and the year of a given entry may not be

clear.

14 Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version

7.2, 03 December 2015), September

1818, trial of

WILLIAM SADLER (t18180909-92).

15 The Poll Book, for Electing Two

Representatives in Parliament for the City and Liberty of Westminster,

June 18 to July 4, 1818. 235 pp. London,

1818. p.181, “Durham, Thos. 7,Dean street,

Shoemaker”, ”p.xii errata

on p. 181, for Durham, read Dinham”. Google Books, Verified 5 June 2017.

16 1841 Census of England TNA

HO107-738-7-16-24

17 1851 Census of England, TNA HO107; Piece: 1559; Folio: 133; Page: 36; GSU roll: 174792

18 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, p. 231, no. 1848 & p.232, no. 1849

19 1841 Census of England TNA

HO107-738-4-14-20 & 1851 Census of England HO107-1479-687-27

20 London, England, Marriages and

Banns, 1754-1921, Register of marriages, P85/MRY1,

Item 398.

21 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, Marriages 1828, p.175, no.524.

22 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, 1825 Marriages, p. 268, no. 802.

23 Register: St. Margaret

Westminster, 1830 Marriages, p.76, no. 39.

24 Last Will and Testament of Thomas Dinham, Proved 27 March 1822, TNA Public Records Office,

Catalogue Reference: Prob 11/1654, Image Reference 246.

25 London Metropolitan Archives,

Saint Martin In The Fields: Westminster, Transcript of

Marriages, 1819

Jan-1819 Dec,

DL/t Item, 093/025; Ancestry.com. London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921.

26 Register: St. John the Evangelist,

Smith Square. Baptisms 1801 p.50. No independent

evidence of

parents’ names, but DOB (1800) agrees

with census returns.

27 1841 Census of England, TNA

HO107/737/12-8-4

28 1841 Census of England TNA

HO107/737/21/5-4

29 The Grey Coat Hospital, website http://www.gch.org.uk/school-history.aspx. Sketch in Fig. 34 from Edward

Walford, 'The

city of Westminster: Introduction', in Old and New London: Volume 4 (London, 1878), pp. 1-

13. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol4/pp1-13.

30 1851 Census of England, TNA

HO107/1479/501-16 & 17

31 1851 Census of England, TNA

HO107/1479/332-48

32 1861 Census of England, TNA

RG9/50/113-27

33 1861 Census of England, TNA

RG9/50/105-42

34 1861 Census of England, TNA

RG9/50/26-3

35 1861 Census of England, TNA

RG9/315/153-4 & 5

36 1871 Census of England, TNA

RG10/99/13-17

37 1891 Census of England, TNA

RG12/24/49-6

38 1881 Census of England, TNA

RG11/114/110/29

39 1881 Census of England, TNA

RG11/115/95-35

40 Riello, Giorgio (2002) The Boot and Shoe Trades in London

and Paris in the Long Eighteenth Century.

Ph.D. Thesis, University College

London. Xvii+374 pp. Downloaded 12 Dec 2015.

http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1317575/1/252007.pdf

41 Goodway, David (2002) London Chartism

1838-1848. 352 pp. Cambridge University Press. (especially

section on boot and shoemakers

pp.159-169).

42 Mayhew, Henry (1850). Labour and the

Poor, Letter XXXII. The Morning Chronicle. 4 Feb 1850. (Viewed

in The Dictionary of Victorian

London, http://www.victorianlondon.org/mayhew/mayhew32.htm, 15 Dec

2015.

43 Mayhew (1850) ibid.